Starting from the time when I was in high school in Salt Lake City, Utah, through my college years at Berkeley, and even while in pediatric residency at Oakland Children’s Hospital, I struggled to understand the link between the material learned in books and the needs of the world around me. What was the glue? What was my role? Why was I having such difficulty drawing the connection?

Well I’ve just decided the third good thing about becoming old(er). There are only three: 1) Access to a large(r) community of learning and support, aka connections. 2) Confidence about knowing what is bullshit pretty much as soon as you step in it, and 3) Having the ability and confidence to act on what you believe.

So in 2018, I started a company called Walking Doctors, WD for short. The mission of WD is to make doctor work faster and safer while helping communities understand the value of their health care investments. We started in places where the right decision and resource protection were a matter of life and death— Liberia and Indonesia. These places by the way are among the last places American investors want to put their money, ha! I refer you back to #3 on the only good things about becoming old(er) list.

This is the problem: There is too much for doctors to know. At last count there were 20,000+ diagnoses and 5,000+ medicines. As a result, 20-40% of doctors’ decisions are wrong. Abroad, this proportion rises to 40-80%! One would think that these numbers would cause outcry, but few understand the gravity of the problem because the stories of patients are literally trapped in the current medical record. Medical records are kind of like Trump’s tax returns in this regard: Not constructed or intended for scrutiny. If this rate of error were known, and by analogy if people saw the President’s fraught financial accounting, you better believe things would change.

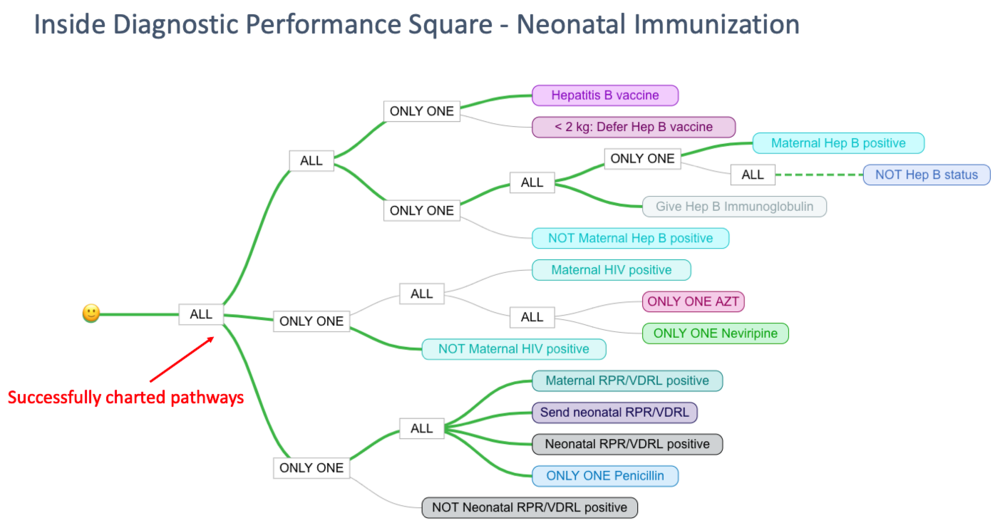

So WD helps the health care provider at the point of critical decisions. Right when the provider think s/he has the right diagnosis or treatment, an evidence-based checklist pops up to confirm or challenge the providers’ assumptions: Is the patient’s history consistent with the chosen diagnosis? How about other diseases that could explain the patient’s symptoms? Is the prescribed dose of medicine correct? Our checklists when filled out even draw figurative paths for the provider illustrating whether or not the totality of decision making is correct. We call this the game-i-fication of medicine: The provider is challenged to comply with the care standard to receive a higher score, which includes a smiley face. Saving lives can be fun!

I experimented with my first paper checklists in Liberia while I was with the non-profit organization, the International Rescue Committee, in 2011. Liberia is a country with only 125 doctors; where 7 in 100 children won’t live to celebrate their 5th birthday. This is 100 times the child mortality rate of the U.S. I quickly saw that an entirely different approach to health care improvement was needed. So at each health facility I visited, instead of submitting to the usual everything-is-fine-please-come-this-way-Health-Director tour, I would spend my time building shelfs with recycled wood; drawing labels for “pneumonia”, “malaria”, “diarrhea” and “sepsis” in uncharacteristic fine print; Xeroxing hundreds of checklists at the local business center— a.k.a town bar with dirt floor and spiders; then stacking the checklists into their respective cubbies as if serious health cash. After that I would work with clinical staff to model their use into the wee hours of the night. From that experience I mostly remember quiet with the occasional moan and mosquitos. Using these non-traditional techniques, IRC teams dropped paediatric mortality from severe malaria by 30%, as one example.

By 2015, technology had caught up. Not only could I avoid the chaos of paper by putting my four checklists onto the computer screen, but I could recruit communities of doctors— often from living rooms on opposite sides of the globe— to construct checklists for virtually all medical conditions. These computer-based checklists had the added power of integration: They were alive. For the individual doctor when filled out, the checklists could simultaneously write and store the medical note; do the billing based on care received; manage the pharmacy and drug stock, and quickly construct monthly performance reports for higher ups. Bottom line, we could improve doctors’ bottom lines!

For managers and leaders of care, the data compiled from our checklists presented a first-ever view of how patients were doing within facilities and across regions; where and what top medicines were being prescribed (and running out); and places disease incidence was too high forewarning of epidemics. Remember how I mentioned how difficult quality assurance is within the traditional medical model because patient fates are literally trapped in the medical record? Well we built a system that could securely share the collective impact of each patient’s story, how they were treated, and what ultimately happened with a click. Okay, two clicks. This promised enormous implication to health care and public health systems everywhere but particularly to middle and lower income countries where there are few second chances. This way too societies didn’t have to just take the doctors’ word for it that they were doing there best jobs.

There’s still much to do and more to describe but the following captures the dusty book to real world concept about which I began. Here I am speaking at the incredible bastion of higher education: Harvard Medical School. But I am talking amongst friends and about the impact Walking Doctors is trying to make for people I’ll spend a lifetime knowing.